Rafael Torrubia

Writer/Poet/Optimist

About

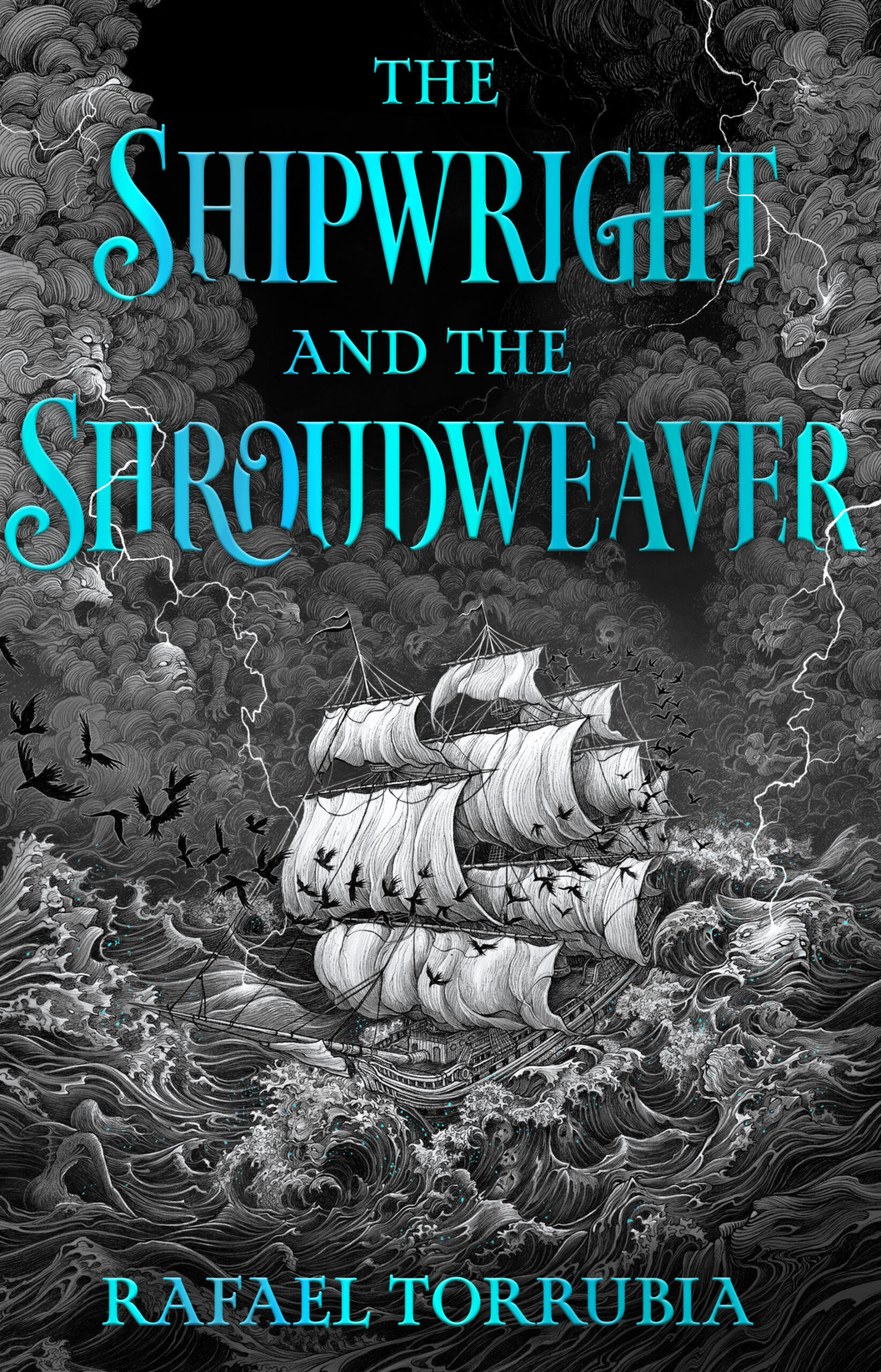

I'm a writer of epic fantasy, poetry, history, and things in-between. My debut novel The Shipwright and the Shroudweaver is out November 2025 from Gollancz. I currently work part-time with the University of St. Andrews supporting postgraduate students, and also with the writing charity Open Book, delivering creative writing workshops to participants across Scotland.I have won a number of awards for my writing and poetry, including Unpublished/Published Writer of the Year from the National Gallery of Scotland, the Deirdre Roberts Poetry Prize, and multiple shortlistings for the Bridport Prize. I'm represented by Jamie Cowen at The Ampersand Agency.

I'd be delighted to hear from you.For publication enquiries, contact Jamie Cowen, The Ampersand Agency.

Pendulum Magazine, October 2025

Hey, It's OK

Poetry Scotland No. 106, October 2023

Maps Community Project, Open Book, 2021. Listen here

The Heart of the Swallow Queen

Corvid Queen, Sword & Kettle Press, 2021

congregation

Claw & Blossom, 2021

Thrice

Bloodbath, 2019

North.Alpha

Amplify, 2018

Grateful Scraps

Well Done/You're Welcome Zine, 2017

Prophets

Jupiter Artland, 2016

Home

Homecoming Zine, 2016

Fox Gospel

Edinburgh Fine Art Library, 2012

Venus

Words On Canvas, National Galleries of Scotland, 2010

125th and Lenox

The Scotsman, 2009

My most recent academic publication is Black Power and the American People which traces the long history of the black power movement from plantation folk-narratives through the iconoclasm of the Harlem Renaissance, the battleground of the American campus, the struggle and skill of the Negro Leagues, the drama of the boxing-ring, the killing fields of Vietnam and the cold concrete of the penitentiary, right up to the soaring sounds of Detroit techno and the electric imaginings of Afrofuturism. It can be bought direct from the publishers, or from Amazon.

"With eloquent prose and analytical precision, Rafael Torrubia brilliantly illustrates the significance of Black Power as a “revolutionary cultural concept”.Challenging conventional periodisations and narratives, Black Power and the American People connects a diverse range of individuals, movements and moments to show how self-determination has always been a central demand of the African American freedom struggle.This is essential reading for anyone wanting to better understand the complexity of Black Power and how the movement continues to resonate today."― Nicholas Grant, University of East Anglia, UK

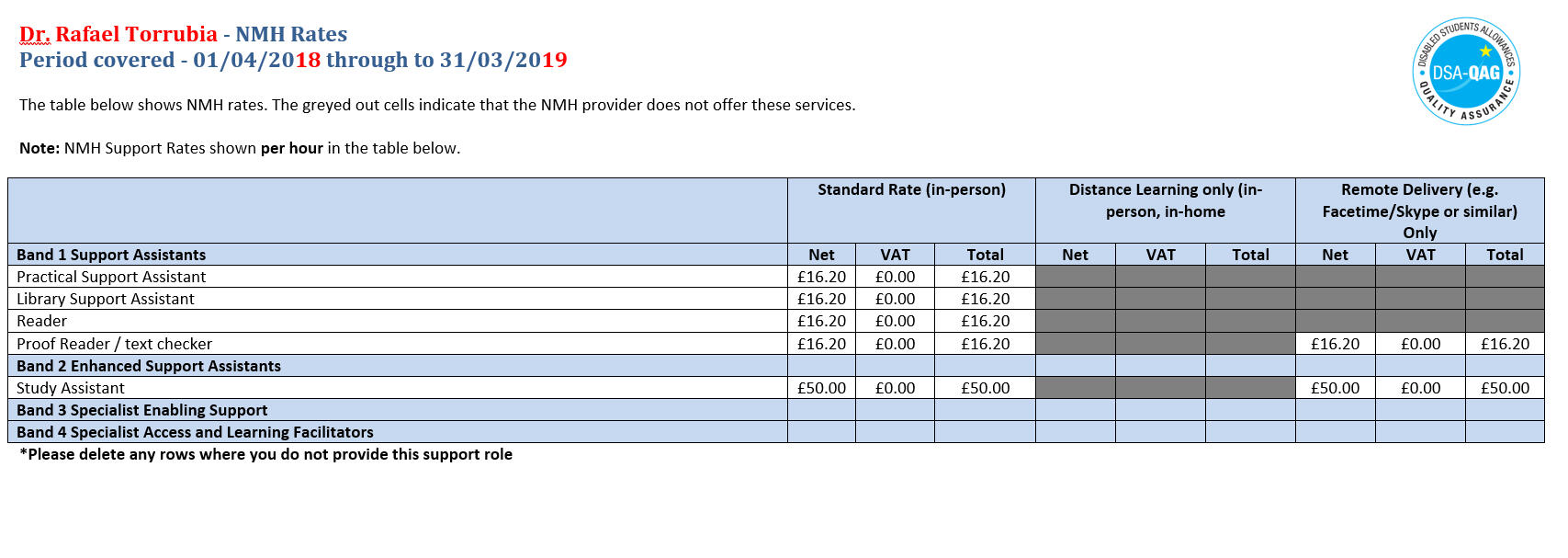

I offer both SAAS and SFNI supported, as well as bespoke, mentoring services, designed to help students with any challenges they may be facing in their studies. I have particular expertise collaborating with students with ADHD/ADD, depression, anxiety and other conditions. Private and DSA rates available on request, so please drop me a line!

I offer a bespoke editing service for academic and fiction manuscripts, monographs, theses, and essays. I have over ten years editing experience, working on major manuscripts, journal articles, ScotGov documents, and a variety of student theses, and I am proficient in MLA, AP and Chicago-style citation amongst others.Please contact me to discuss an affordable rate for your project.

... superbly reliable and efficient ...

... The technical details of my dissertation were rendered pristine...

... I have never experienced an editing process that went as painlessly and quickly ...

.... suggestions as to style and content were insightful and a great help....

... My editor remarked that she had seldom come across drafts so perfectly presented ...

Postgraduate Administrator, University of St. Andrews

October 2020 - Present

Public Lecture Programme Coordinator - University of St. Andrews Open Association

October 2019 - October 2020

Course Coordinator and Lecturer: 'Understanding America', St. Andrews University Open Association

September 2018 - Present

British History Programme Coordinator: Oxbridge Academic Programs

June 2015 - Present

Social Sciences Lecturer (Part-Time): University of the Highlands and Islands

November 2015 - Present

Diploma Examiner (History): International Baccalaureate

May 2014 - Present

Lecturer: Department of Modern History, University of St Andrews

May 2011 - December 2015

Teaching Fellow: Department of Modern History, University of St Andrews

February 2009- May 2015

Undergraduate Studies Advisor and Matriculation Official: University of St Andrews

September 2014 -February 2016

The Shipwright and the Shroudweaver

Forest Secrets

autumn will come

what we learn in the dark

buzzardland

ink

the blood

the dead

fricative

a thing that dreamed of trees

strygă

the avoidance of sound

a light

summer collides

so much happiness

receive/transmit

go

MERRY SWUSHMAS

a thing that dreamed of trees (ii)

journeys into quiet

sausage roll

congregation

songs of scotland

winter

sealed

snowdrops

yorkshire

it begins as a house

glenstal

the second half

Prophets

museumite

lang cut

grateful scraps

trespass

north.alpha

coach

your teacher means well

soul/field

hawser & salt

cuatro etapas

office

thin dark boats

jailbreak

menu de los dias

avenencia

cracked tooth

donkey

the sea captain's daughter

the three dogs of the huntress

the heart of the swallow queen

a friend

owl's table

little duck

cart (I)

unravel

cart (II)

dig

13

break-in

torre

formica

pines

drum

long-day-at-the-office

gilding the monkey

summer house

the absent king

three drawers

low red

reprimido

houlet

w;o;l;v;e;s

postcard

memoria

My family tell too many stories, wide-mouthed and Spanish. So many that they’ve fallen into my head over time, like frogs into a pond.

The frogs surface occasionally and croak little lies. They say I was there in the field when my cousin drowned, slipped deep into a drainage sluice, hands grasping against the light.

I was not. I cannot remember wet fingers or wide eyes, but I feel like I do.

I keep the toy motorbike he gave me on the shelf, green as a beetle, rusted to nothing.

The frogs tell me I saw my father fight a bull. I did not. I wasn’t born, but I can still hear the hot-sun crowd, still see blood on the sand every time his fingers run over an old horn-struck scar.

Go and open the door.

Go and coax the fire from the grate.

Take it for a walk, let the tips of your fingers brush the coals.

Go and open the door.

Let the teacups hatch and scatter the shards of their shells in the garden, until the sprouts come up.

Go and open the door.

Unravel the cat and give it a good dusting.

Knit some kittens from the old yarn and put them in your back pocket.

Leave one on the stile for when you pass in the morning.

We are looking at two kittens.

One ginger, one black. They do not look like they are having a good time.

One is wearing a blue ribbon, one pink.

The kittens’ ears are bent at the corners where the postcard is weathered.

In red and white text, the postcard reads: ‘A fine old time in Cornwall.’

There is a stain on one corner. Hopefully, it’s chocolate.

On the back there are two stamps and, neatly lettered, an address.

The postcard reads: ‘Dear Mary, I hate it here. All the boys look like wet fish and the air tastes of salt. Can’t wait to see you when I get home.’

I’m an indeterminate age.

I’m an undetermined age,

I am dreaming, and in the dream I am asleep.

I am asleep in the window of my parents’ home.

On the window seat, which is beige, or might as well be.

The curtains are drawn but something moves beyond them, like blood under skin.

Shadows bruise the fabric, which bellies outward.

I am asleep, but my fingers fall outside the curtain.

Brush the hem.

Soft, dreamlike.

Until something else touches them

A tongue, then teeth.

Takes my hand in its jaws, and bites down.

Slowly.

Irresistibly.

Hard enough to bruise the bone.

snowdrops

and the green

and the trees

and the wet

and snow drops

and the earth has

forgotten freeze

and aren’t we lucky?

and isn’t that a joy?

and isn’t that

snowdrops

The songs of Scotland are muffled in the dark, beneath blankets, in the back of the car. The neon of the motorway’s light flickering against half-closed eyelids.

The songs of Scotland are muffled above the frozen roof of the cottage at night, as the sound of owls loops loosely over the tiles.

Muffled on the high slopes of the glen. Wet in the bracken where the deer sleep.

We’ll find echoes of them in the morning, shotgun casings, bare in the grass.

The startling red of a hind with her throat torn out.

The snow has fallen and lain, fallen lead white and lain.

There is a lid on the world, it’s been sealed away, and the only flurry left is snow on snow.

Ice atop, and ice beneath.

Seems a shame, to move across it.

Seems a shame to bring a body into this.

To be a person amidst all this white.

All pulse and breath and blood.

Hard to be still like the snow.

Hard to be sealed away.

Hard to be still when the world keeps running.

How lovely these journeys into quiet

How lovely the last breath

and how holy the first

we sing to ourselves as the planet is burning

I sing to you as your hand slips from mine and the sea rises to the horizon

the quiet comes after the song

as the ash falls from Amazonian trees

as the waves push beaches down into gravel

as we raise fences and cages

but still

quiet lives in these spaces

in the strips of shadow on the tops of the waves

waiting until we find the song

eat

drink

sweet

I cannot eat membrillo for it is full of ghosts.

I don’t know at what point they get in there.

I wonder if they come in with the light, if they crawl down the rays of the sun and into the leaves of the plants and swell up the stems and wait, and wait, and wait.

Until finally they push out into pulsating yellow fruit.

Perhaps when you pick them, you can hear them inside.

The ghosts, I mean.

Shake a quince in your fist. Listen to the spectral skull of your great-great-grandfather pinballing off its wet little inside.

Maybe if we juiced the fruit, the ghosts would flow out, slow and sticky as wine.

It’s possible the ghosts get in with the light, but if they do not, then I think they come in with the boiling.

As we all know, boiling creates steam. Splitting the air with water. Veiling it just enough that spectres can move through.

From the beyond, or the spice cupboard. I don’t know. I don’t know where they come from.

But they get in there.

You can see them. Even when you stir the syrup, the briefest ripple as the hand of your cousin, the one that drowned, surfaces above the roiling pulp and gives you an inappropriate thumbs-up.

But then, he was always an optimist. Smiling even as the water took him.

So it is possible, that the ghosts get in with the boiling, or with the light.

More likely though, that they get in with the pressing, and the chilling.

The dead love the cold? Is that not the truth?

The dead love the cold almost as much as they love you.

So it’s no surprise that they sneak in. Congealing in the freezer.

Lay the plates carefully or you may find fragments. Of an aunt, an uncle, someone more distant and less defined perhaps, but fragments. Crumbled in the ice-cube tray. Stuck incongruously. Gelid and silent, and really, judging a little more than they should.

More than is fair.

It is not your fault. It is not my fault that I cannot eat membrillo, because it is full of ghosts.

Because, you see, listen, please. Because, you see, if they do not get in with light, or the boiling, or the chilling. If they do not, they get in upon the blade of the knife.

So, you cannot even cut it. You cannot even savour a s ingle small sugared slice without the taste of your grandmother’s disdain. And does that not spoil a meal, a midnight snack, even the lightest of lunches?

I cannot blame them though, the ghosts. And neither should you.

They all left so soon.

They all left yearning. they are all drawn back inexorably, to the light, to the air, to the briefest sweetness. To you.

God, if god is a flavour.

Incense, sweat, sugar, blood.

Coffee. Boiled milk.

Anise at sundown.

Split seeds, white teeth, black veils.

Rosemary burnt by the sun

White stones, goat meat.

Crushed ants, cat food.

Rooster feet.

Sherry, bull’s blood.

Arcs of air.

Hot leather, prawn shell.

Storm fallen orange.

The plaza.

Fish bones, cat bones.

Burnt tomato mornings.

Barbacoa, turned rice.

Peaches melting in orchards.

Sheep stink.

Tire oil.

Asphalt and salt.

Chilled wine

red tongue

hot foil

night

We took it for granted. Let it slip down our throats without an edge of benediction.

Grabbed ourselves one bottle every year.

Half the fun in the holding of it, in the curves of it.

All that smooth glass filling our young hands.

The liquid inside not an afterthought but, you know, a different stage of the trick.

Year after year we took it for granted.

And if our hands got older, the glass stayed the same.

And still, we were steady on the cork, and confident breaking the seal.

We picked red from under our nails all through the night.

Clapped each other’s shoulders, felt the planes of the backs of our friends move

in the firelight, in the warmth

refilled, and poured, and poured again

again, again! if you can believe it

and god if we weren’t wanton

and if we didn’t want to be wanton

and if the wanting that filled us wasn’t washed away

by every tip of the squat neck

and the bright rim

o friend

we took it for granted, again

and again, if you can believe it

one bottle every year

and if those of us that gathered round it shrank

as we drank, then

who was counting, you don’t count death,

not at a time like this

not at a time like that

not anytime you can get away with it

every hand a cup

and every cup for the filling

and maybe a bit of us

as we were filled

maybe a bit of us flirting

with what that meant

with what it cost us

to pour and drink and pour again

and yet, friend

you know the tale

we took it for granted

year after year with

wet lips

steady hearts

year after year

after year

we took it for granted

half the fun in the holding

and half in the drinking

until we realised

of course, of course you know

until we realised that we had got our numbers wrong

that the world had been doing its own counting

and what it had tallied

wasn’t just numbers

but something else

another little cost that ticked

with every tip and slip

that we never even counted

never even countenanced to count

as we drank every drop in the

light of each other

never pausing to wonder

how much our thirst

had cost us

how little was left

in that beautiful bottle

we had drained

to dry

Merry swooshmas

a huge woosh and a

huddadadudada chonk to you

and all your flimp-flump family

Last swooshmas, SO merry

swooshed so much

swooshed chipolata

shoomp-shoomp-shoomp-shoomp

swished brussels sprouts

abingabungabingabungasqwunch

swushed even a whole turkey

wawawawawaaaaaaaaaaaaKTHONK

This swushmas

very serious

all plugged in at the wall

Nowmorraneva, intheeztryentimes

Nowtryinmorraneva in these now times

Now times now now now

evernow ever

BUT

still swushmas

get a clunk-click

get a vwommvwomm

get a rattle and a chunk

swushmas means swush

swush a canape

aflempaflempaflemp

swush a prawn

Abbrtrt – flehh

swush the swushmas tree

abwangbwanbwangbwang crunch

but now

morranever

swush those you care about

and swush each other

Car crash eyes

eyes like wet-dipped rocks

a shriek like a mother that’s lost her child

sometimes

or

soft and low beneath the moon

an underwood lullaby

a head on an eternal pivot

radar dish bones

and feathers softer than sleep

the stoop of it into the corn

a diver in black grass

small lives plucked from between the stems

swallowed

coughed up later in neat packages of

bent fur

and bone

A low red, hung on the edge of hills burnt down to dusk by the falling sun. Like a guttered wick, the stub of a struck match.A low red, slicked across the sodium streets. Licking the dog-tongue gutters and pooling under the wheels of cars.A low red, coughed up on the banks of bridges, spat into dark water.Swilling away from light, somewhere into the black below.

The snow has fallen. Fallen and lain.

He digs. He digs though his hands are raw.

Huffs on his fingers, mutters to himself.

Digs into the earth, black and cold and unforgiving.

Roots turn the metal of the spade, slip from under it like an unhappy lover.

Still he digs, the blade punching down through the frost.

The dog has been lost for two days now, the hearth bare and empty.

He doesn’t hold much hope in his shivering heart, but he holds some.

So, he grits his teeth, huffs on his hands and digs.

There’s a summer house at the bottom of the garden that sings in the morning.

When the light of the sun hits it, it sings a quiet little song, like the background hum of a half-heard radio. The seedlings turn their heads to listen, shifting in the warm soil.

When the sun hits, the old mug rings, the mud on the mat dances. The summer house thrums, like the chord of a guitar struck by fingers that are half bees, half starlings, half the shift of honeysuckle against the blue sky.

Next to the summer house is a garage, harled into greyness, its varnished bones holding up wasp nests that blossom like sizzling flowers in the pine-stained dark.

It remembers resin, and sawdust, and the cut of the saw that came before.

It remembers holding the spades that turned the earth, the wheels of cars that rolled in and out, crunching gravel into rose pink puffs.

When the summer house sings, the garage moves its plastic tub memories on its black steel shelves, looks out the window at the garden and listen to that old familiar tune.

There are three drawers.

One for sweaters, woolly jumpers. General knitted things.

One for t-shirts, sorted by colour, rolled because you saw Marie Kondo once and thought it might make you a better person.

One for socks, underwear. Unrolled because there’s only so much time in the day.

Let’s leave that drawer for now.

The jumpers get folded, arms behind the back. The way your grandfather did it. Like you were going to lay them out for a small boy going to school.

They should smell of nothing except wool, detergent and a few persistent memories.

The t-shirt, as I mentioned, gets rolled, although it doesn’t make much difference.

Select them out by colour, green and yellow for good days, black to feel safe. Blue when there’s nothing else left. Pretend you’re going to throw the blue ones away.

The sock are chosen by colour. Don’t get too attached to the first pair. You’ll get wet feet when your Dad over fills the kettle, when you step too close to the dog’s bowl.

Pants are pants. Match them to your t-shirt, because even if no-one sees, it’ll put a secret spring in your summer step.

I never feel more Scottish.

The first when I was four.

Fell's the bakers.

Glass smudged by fingers.

A treat, half paper, half pastry, half hope, half grease.

Slippery from the heat, from the knowing.

Nowadays, I buy them when I’m tired, when the streets are dark.

A treat, half paper, half pastry, half hope, half grease.

The tops of houses, flecked with pigeons and satellite dishes

receiving the sound of the street

newer glass skewers the brown brick

holds the sun as it falls

somewhere, a dog

somewhere, the shriek of children

somewhere, your mother is calling you home

somewhere there is light

somewhere laughter

somewhere the hiss of the TV screen

the tops of houses, flecked with pigeons

the static of the city

the satellite dishes

the weeds between

receiving

transmitting down into the dark

There is a thing in me that dreamed of trees.

There is a thing in me that dreamed of birds.

There is a thing in me that dreamed of stones, and the rivers that ran over stones.

There is a thing in me that dreamed of night

and a thing that woke at morning

a thing that felt the sun

and a thing that fled the rain

there is thing in me that

left the forest and a thing that

called it home

Like distant ships in mist, or bells

the ghosts of the dead are leaving at lastunskeinedevery filament of their bodies given up to sea foam

or wandering onwards to lightyour late father’s hands and his tartan legs

vanish in a spray of gulls

your mother stoops regretfully below a cormorant’s wing,

before leavingthe sky unspools for them, these dead

their feet still damp from river water

crumbs still on their lipsthe sky unspools for them and

they do their best to leave

or to make their leaving seem like a half-closed dooryour small brother ducks beneath the prow of a tug boat

floats until the propeller spin drags him under

leaves as little bubbles of light

laughingLike distant bells, or ships in mist

the ghosts of the dead are leaving

and the quiet behind them does nothing to mark their passingjust moves in the kelp on the seashore

on the wings of the gulls

and down the backs of the buildings

as the city slides to night

there is a light that is lit on the islands, and it call the sailors home

there is a light that is placed and spun in glass on the edge of the salt

as the earth falls to water

as the lands falls to the seathere is a light on high,

seagull-struck

and there are lights below

candle-struck, warmed through

rippled glass and held between wearying handsthere is a light that hangs on the edge of prayer

and a light that falls unheard into the breakers beyond

there are lights that are lost and lights that are kindled and there

are lights that keep the stars pinned highas the earth falls to water

as the land falls to sea

Newly discovered in the sky

a constellation, the Absent King

To the east, four stars forming a scepter, dropped. Signifying abdication.

At the northmost point, the planets Pelageus and Acheron, forming his split crown

On the west, the five faint lights of his hand, spread wide.

For this reason, he is known in the far realms as the Beggar, and signifies despair.

In the center, the burning remains of the dead planet, Oresteia.

Still smoldering, eons of red light forming the last blink of his eye.

Bring down the lights, bring out the drum. That big one with the ceaseless beat. That thrumming thump which screams of old cinema, MGM and the lion’s roar.

Roar yourself, open your mouth and let go of the last bit of control.

Bring down the lights and curl up in the dark.

In your new lair.

With only the sound of your breathing.

Your breathing and the drum.

The drum, your thump, your heart, the drum.

Gilding the monkeyTo fete someone far beyond their accomplishments, skill, talent or appearance.Positive – “I thought having the janitor helm the parade would really be gilding the monkey, but his trumpet skills were incredible.”Negative – “I can’t believe the Whitehouse staff have been gilding the monkey for four long years.”

There is a thing in me that dreamed of trees.

a wet and wild little thing, a half-chewed bird hung behind my heart

that shivered when my lungs shivered

that found a voice in the sun

in the driving rain

in a storm, in that cattle-herded roll

over the tiles of my town

the tops of my teeth

a thing in me that dreamed of trees

that sought them still

even in cities

even in fire smoke

even when told it was home

The first thing you saw were the towers, held red in the light of the setting sun.

The sound of the song that flowed from them, the language of blackbirds poured down hot stone.

I remember my mother’s voice, balanced on the edge of the well, dipping into the water.

When night fell, the branches of the trees unfurled and gave up lizards, small and fast.

I remember waking in the night to one balanced on my ribs, feeling its small claws tickle my throat as I looked into eyes that twitched like wet amber.

Walking into the streets at night, I saw other lizards in cages. Piled atop one another. I imagined I could hear their hearts hammering in the flower darkness as they strained against the bars.

Seeking the insects that flew under the unfurled branches, fading in the last red light from the singing towers far above.

a composite found poem made from whole and half-remembered lines from my Open Book writers,

plus some new connecting tissue

charter-driven

nettle-sting the skin

gorse & cuttingthe songs always tell a story

hum quietly in rain and patience

two men with sten guns

lightning waltzthe carriage of galaxies

where no great tree could ever grow

much to see in the evening lightthe road bridge stands

winter has played its last pack of cards

folded gently into the embankment

hollow reeds and crumbled brickthe geese know

balance

equinox

darknessthe decay of greenness

it is after all, a passingthe world is ripe, overripe

salty sliver

men disgorging in the gap

key in the door

eating rhubarb

oil drums and planks and sailing on the Tay

the smell of steam trains

buildings slam against buildings

perceptual shift

coloured lenses

stained glass

swirling, lashed, continued

shape and colour become impactwandering streets cast their eyes on the sea

and find it changed

they are building a space station under the rowan tree

a foxhole of flowers

and emails in the half darkendless church Sunday

grass for grazing

teal mixed to paste

as yellow birds fly pastpudgy, soft hands

strange and unreal

someone’s bigger plans

speaking through the housesoundless as the season

a wounded day

a workshop full of the past

of skin retraction

and myths undergroundwe follow still, muted

it’s an even pounding in 2/4 time

punctuated by the saliva that

drips to the ground

the respiration and drag of pebbles

silt and stone

Skeins of geese write a word across the sky

and the word is winter

not winter as we know it

but the winter of birds

the winter of a magnet in

the heart, singing South

pulling hard against the breastbone

and drumming in the blood

as wings lift the lips of clouds

as feet touch the edges of the sea

as the compass needle shifts, twitches,

yearning towards home

The track vanishes into the pines. I can’t count them. The track vanishes into the pines and the dry stone of the riverbed twists under my feet.

Insects in the air, and fish in the water. Salmon, maybe.

Voices in the trees, distant.

Searchers.

Ghosts of celtic warriors orienteering around their graves.

The track vanishes into the pines. Small black frogs amidst the needles, ditch-wet.

Watching every step, trying to keep their little hearts alive.

Down the river, herons, and in the woods, foxes.

They’re probably doomed anyway.

The track vanishes into the pines, and their branches knock against each other, calling home.

the sounds here are built on the avoidance of sound

life steps around noise

life moves within the quiet like slow water

over stone

the silence is for the benefit of God

which is to say

it is for the benefit of people who believe in God

for people who wish to breathe

in quiet

for people whose blood moves like a held breath

there is a sound here but it

moves in the exhale

in the bending of the birch

in the rain that falls into gutters

cupped like hands on the edge of grey stonesound flares briefly in the embered heart of a log

it hangs in the fire-smoke

and stings the reddened eyes of the sister who kneels

who moves small sounds in the knocking of rosary beards

sounds lingers residual in the organ pipes

music the same colour as the painted roof

music that evaporates as the day unfolds

scattered notes that gathered by magpies

and flown on the clatter of their wings

out beyond the bend of the birch trees

and into the wider silence beyond

It had been a long day at the office.

Ghosts and whispers around the water cooler.

Knocking back little plastic cups full of memories.

Collecting babble in ring binders and filing them in echo cabinets.

It had been a long day at the office, xeroxing my father’s memories until they faded into grey. My fingers getting blacker as I worked.

At the office, a long day, making spreadsheets of fragments. Tallying up the scraps of old lives and seeing if they still took the shape of a person.

Long office at the end of the day, trying to find some sense amidst the shards.

The day of the office, long at the end.

My house was broken into yesterday.

Lost four jackets, some cash.

Not that fussed about the cash.

But the jackets.

It’s strange. It’s stupid. I know it’s stupid, but there were jackets I could remember wearing on holidays, with family, holding hands on frozen walks, getting soaked through until the wool stank like a wet dog.

So, the jackets are gone.

The memories, I know, stay.

But for a moment, it feels like someone has touched them, like a ghost slipping into my past life.

Like an uninvited spirit at the bottom of the bed.

‘I have tried to see you thirteen times’, he said.

‘Thirteen times?’ I replied.

‘Yes’, he said.

‘I would apologise’, I said, ‘but I do not care.’

‘Or rather, I am incapable of caring.’

His face soured at that, every line curdling. It didn’t do him any favours.

‘Well’, I said, attempting the shape of something conciliatory. ‘You are here now. What do you want?’ Perhaps a little too much flint in my tone there, as he flinched like a struck snake.

‘It’s my wife’, he began, his eyes running over the jars stacked in the half-light behind my hear.

‘Ah, you want her dead!’ I said.

‘No’, he cried.

‘Disappeared’, I said, smiling shark toothed.

‘No’, he shrieked, his stubby little fingers knitting anxiously.

‘What then?, I snapped.

‘I want her happy’, he sighed.

‘Oh’, I hissed. ‘We don’t do that sort of thing here.’

Owl’s table they called it.

Out back in the woods.

A wet old stump, half sunk.

We used to gather their nights.

Half a bottle of cider. A handful of squashed Lambert & Butler nicked from my Mam’s dressed, and that was it. We were set. Chatted about whatever we liked, who we fancied, who we definitely did not fancy.

Until the night the owls actually came.

Just one at first, speckled, big as your arm. Then a second, barn owl face [lit up] like a starched ghost.

A mouse still twitching feebly in its claws.

We had no clue what to do, so we offered them a drink, a smoke. They took it graciously, clumsily, wings flapping.

Drank deep, and started to tell us where it had all gone wrong.

This table.

This table.

Christ, but I am sick of it.

Do you remember the way he’d stub out his cigarettes?

Those yellow fingernails.

And the formica, jesus, sticky as a week old corpse.

Get Tony Robinson on that, get bloody Time Team.

No, get what’s-her-face off Silent Witness.

Do some digging, you’d find half his good ideas buried under there. Never started.

Och, this table. It make my eyes feel seeck just lookin’ at it.

A’ willnae miss it.

Him though, I’ll miss him.

Grey hair, yellow fingernails, old coat.

I’ll miss him.

In the southern sky, the three dogs of the huntress.

The first, the fastest, tipped by the pole star, straining at the leash.

Symbolising impatience, hurry, imperfection.

The second behind. Its third and fourth paws our sister planets, waxing and waning, never stepping forward.

Symbolising caution, prudence, cowardice.

The third at her back, leash slipped. The stars that fell last year.

Its teeth raised to her neck.

Symbolising war, betrayal, ending.

In the mornings, the rising sun runs along her blade, but she vanishes before it strikes her husband’s heart.

[In Romanian mythology, the Strygă is a vampiric witch created by the untimely death of an unmarried girl, who later returns to consume the flesh of her family. The bite of a Strygă, untreated, turns its victim inexorably into a monster.]They came for her in the dark

bit deep into her soft flesh

and she changed.We locked her in the tower by day

and she roamed the necropoli by night.The peasants loved and feared her in equal measure.

Stories proliferated.A priest arrived carrying a cross of dull gold.

She welcomed him to her chambers

chatted brightly

adjusted her hair.Portents abounded.

The stable hands found secreted

a barrel full of horses’ teeth.

She wept and complained that

the sinks always stank of meat.A mercenary came, grey of hair

eyes of salt and bone.He left a finger and thumb from his right hand

and an antique blunderbuss

bent violently out of shape.She bemoaned her loss and

licked flushed lips

worn ragged from chewing.The kitchen complained of

a plague of flies.

The seamstresses found maggots

woven into their dresses like fine thread.She lay abed and spoke

of dreams of a sullen city

ringed by echoing towers.The peasantry swarmed the gates

with empty bellies

and overflowing demands.Arrows descended from on high

and the dogs slept soundly.She tossed and turned

in the garden hammock.A vase shattered.

Shards sketched red lines

across the hollows of her skin.Soldiers came at dawn

the door splintered

swords scoured the corners of the room.The tower lay barren

all that hungering eyes found

strewn and strung from rafters

were the polished skulls of owls and

the shrunken, withered feet of bats.

How lovely these journeys into quiet

every footfall soft against the tilted steps

that lead up to where the old herb garden was

to the grove where nine birch trees stand

the martyrs of the revolution

in the dining hall, the monks move in a silent dance

their plates laden with garlic mushrooms and a sermon from Cremona

the ex-abbot drinks dessert wine by the fire and talks to a nun

who has come to pray her cancer into the embers

outside in the mornings

the organist, whose name is Love

places holy sounds

to shuffle the footsteps of the boys

back to school

When you came down the hill

you carried your burdens with you

the lights of the house soft in the dark

windows pressed against the night like mouths

tree branches framing the sway of your shoulders

and the wrecked

rusted

red frame of that old bicycle

a wheel listing

slipping on the cold black icethe water runs slow here

thick with memories

eddying deep past the grey slump of the millswhen you were younger

our footsteps stitched the fields at dusk

we kissed with ragged lips

under a moon haloed with barn owlswe were guardians of our own country

held vigil in cricket pavilions candles flickering

as we listened for the sound

of gates swung shut by horse thievesmorning cold rubbed your knees popsock-red

as we shoved frosted toes down the lane

pushing the patent leather boats of our feet

sluggish into schoolrooms

that stank of chalkdust

where even the light was lazy

as it cradled your head

against the name-carved desklater

I walked you home

we wondered how there would be

space for anyone else in our liveswe made a joke of it

I hugged you

your sharp bones and

your hair wet with woodsmokebehind us in the trees

small things moved

fleeing the ghosts of your ancestors

who slid between the trunks grey-skinned

waiting for us to turn our eyes back upon them

My debut novel, The Shipwright and the Shroudweaver is a story of murdered gods and stolen magic where grief destroys the world but love remakes it.Out November 2025 with Gollancz you can preorder it from Waterstones, Amazon or direct from the publisher

A dark fairytale of epic proportions. Torrubia casts a spell with their poetic prose and portrays a strange, magical world full of complex and compelling characters.- J.T. Greathouse, British Fantasy Award-nominated author of The Tower of the Tyrant

Rafael Torrubia pulls you along a dark, surreal, and hauntingly lovely dream over the high seas in this powerful debut fantasy. With prose that's lilting, seductive, and smooth, a story that pulls at your heartstrings like canvas and rope, and a magic as deep and sorrowful as it is fantastic and forbidden, The Shipwright and the Shroudweaver is a gothic love letter to high seas, deep love, and the epic stakes of a world at risk. The spirit of Poe infused with Samantha Shannon, and perfect for fans of both!- R.R. Virdi, USA Today-bestselling author of The First Binding

The most beautiful book I have read in a very long time. Dark, gothic, visceral and incredibly hard-hitting. Rafael Torrubia's prose is stunning and they have managed to render gripping characters in a tortured world that will stay with me for quite some time. A delight from the first page to the last.- Rogba Payne, author of The Dance of Shadows

Forest Secrets is a curated journey through a foreign woodland, an expedition report from the edges of myth. It's told monthly via dispatches of writing and art from Rafael Torrubia and Rowan Heggie.You can subscribe from as little as £3 a month by clicking below.

Thank you for the marrow

(from your bones)

it was sweet

but not as sweet as the edges

(of your smile)

which peeled off

so neatly

thank you for the little

red scraps

which caught

(between my teeth)

they were soft

but not as soft

as

(your last soft breath)

against my cheek

thank you for

(your delicate hands)

your expansive gestures

which rendered down

into

such

(gently digestible)

chunks

North.AlphaIn all things the north wind blew

and in all things we felt it

neither blessing

nor curse

its teeth on our shoulders

as we shuffled beneath the bulk

of our dead gods

we spat on our hands

wound blue rope tight

against raw knuckles

the travois caught on rocks

we broke them

with hammers

when we could not

break them

the children lifted them

and we moved forward

ice on our lips

we walked the wet black of the earth

and imagined that there might be trees

on the horizon

Deirdre Roberts Poetry Prize, 2022Bridport Prize Longlist, 2022Emerging Writer Awards Listee, Moniack Mhor, 2022Bridport Prize Shortlist, 2021Jupiter Artland Poetry Prize, 2016Jupiter Artland, Inspired To Write, 2015Bridport Prize Finalist, 2012Writer of the Month, The Fiction Shelf, 2011Top Ten Writer of the Year, National Galleries of Scotland, 2010Arvon Foundation Creative Writing Fellowship, 2009Unpublished Writer of the Year, National Galleries of Scotland, 2008/2009

Eccles Centre Postgraduate Research Award in North American Studies, British Library/British Association for American StudiesDepartmental Research Scholarship,University of St AndrewsSt. Andrews University Students’ Association Teaching Awards, Twice Nominated for Best TutorBonarjee Research Essay Prize,

Proxime Accesit.

PhD:

‘Culture from the Midnight Hour: A critical reassessment of the Black Power movement in Twentieth Century America.’University of St Andrews

2008-2011

M. Litt. With Distinction: ‘Slavery, Symbols and Song – The Importance of the African-American Slave Spiritual in the Civil Rights Protest Songs of the 1960s.’University of St Andrews

2005-2006

M.A. Hons.:

‘Rhetoric, Reality and Memory in Abolitionist Boston.’University of St Andrews

2001-2005

Congrats on finding your discount code. Subscribe to my Patreon and email [email protected] with the subject line 'Bat-thief' for your unique reward.

half the song is tone

and half the song is body

half the body is a shift into grey

and half is

dinosaurs

remembering to blossom

into birds

all the song is breath from

babies

on the cut of the moon

dipped against night

a song

of tone

and body

stitched against the lungs

against the raised chest

and the arc

of the inhale

all the song is voice and all

voices shift through grey

stepping between the black

of the page, and the white

of the teeth

the turn of the tongue

and the tone of the turn of the tongue

of teeth

of the arc

of the body

and the breath

shifting into grey

The smell of coffee in the cup

The cliché, I know, I know.

But before that, the smell of grounds in the cupboard.

The cedar tang of the wood.

And behind that the smell of the spices that escaped.

Of curry, of ginger, of Christmas cloves.

Scattered like unhammered nails.

The smell of the sun on the windowsill.

the green of the basil expanding to fill the light

hot paint on the fence

burnt rock gravel and the dusty

shift of the starlings

coffee in the cup

but before that

hedgerows unfolding outside

honeysuckle hanging like spiderweb

over the gasoline trail of dirt bikes

cutting down country tracks where the skylarks sing

over the malted heat of the barley fields

into the cool, sweet purple

of the evening dusk

The north winds used to find her on the old cart road, her shawl pinned back against the curve of her skull and her lungs rattling with the ice that hung on the edge of the wind.She walked the black earth of the track half by memory, half by the ruts her feet had worn in the years gone by.Thin soles dancing around sheep shit and gull feather.We opened the door to her every year, rolled the coals in the embers and let her cough small damp gasps into the belly of the stove.She talked little, her fingers knuckling over the frayed hem of her skirt, and we let them wander, happy to see the shape of her against the shadow of the flame.She rose only once, to look at the photo on the mantel, to turn it against the light. Watching the faded shapes that lingered behind the bubbled glass.She left soon after that, the door hitting the frame before the chair had stopped swinging.Picking her way back up the track, back bent against the wind, her bones slowly rolling ever closer to the dark of the earth and the salt of the sea.

The cart always comes from the east, following the sunrise, chasing the first rays of light down the old sheep track, past the stile, still canted and torn by the winter storms.One axle lilting under the burden and the noise of its wares hollering its arrival long before its iron-shod wheels roll into view over the wind smoothed stones of the hillside.Its driver perches up front, whistling brightly, as if he held a bird between his teeth. The soft brim of his hat catching the rising sun, letting the light slosh for a minute in its velvet folds.I open the door as soon as I hear the sway of the axle, the clang of copper pans, that bird-tooth whistle.The horse’s hooves hold the mud outside the garden path, pin the wind to the stones. Its thick, fly-bitten flanks heaving with the effort of hauling so much junk.The driver doesn’t ask for much. Spits in the dust, holds a hand out gratefully for a cup of water and some bread.Touches his fingers briefly against the little of the house and moves on before the last bright rays leave the sill.

She spits and polishes. First, the little duck that her grandma gave her, sitting on the sideboard. Next the silverware, or as much of it as she can stand.The cloth greys quickly, and blackens after that. She can feel the whole sideboard shaking, cups and plates rattling against each other like skeletons left out in the cold.The machines have started again, iron claws shearing into the rock of the hillside, tearing loose the grass, the dark earth, the roots that lace it beneath.Kicking up soot into the sky, all of them.Give it an hour, two at the most, and that soot will sift down the valley, covering the leaves at first, then the shingles, the sheets on the line, the silverware, and finally, inevitably the duck.She coughs softly, picks up the little duck and turns him. He can breathe for just now, even if there’s a wee chip on his beak. She gives him a kiss on the top of his head, blushes at herself for doing it, then shakes out her cloth and moves down the line, as above her the busy, moving metal grinds the hills back to dust.

I have a friend. A friend that no-one sees. A friend that lives on the back of my eyelids, who speaks only on the outbreath.I first met them down by the old shaleworks, a rainy day, and the pool of the pit filled by black water.They say three boys drowned down there in the 70s. Knocked themselves over larking about, and tumbled down, stone over bone, into that dark water.They say three boys drowned down there, and mothers tut into their shawls.They say three boys drowned down there, and fathers tap their pipes meaningfully.I asked my friend about it on that rainy day, and he answered in the squall of the wind.His small bare feet toeing the edge of the salt circle. His little blue lips just resting on his face.I felt sorry for him, standing there above the black water, wet hair drip-dripping down the nape of his neck.So I took his hand, his cold little bones against my warm palm, and lifted him over the salt and home.Now, I have a friend. He keeps quiet to himself, tight behind my eyes.Except on the storm days when the lights flicker and the kitchen tiles sound to the drip-drip-drip of black shale water.

it begins as a house

as house in the swamp

as a house in the haar

as a house anywhere

it begins with a knock on the door

it begins with a shouted hello

and from there it spreads like algae

webbed inexorably over the surface over the surface of our lives

the first act clings to all the acts that follow

and the first scene of the play is never really left behind

our minds hold memories softly on the backs of our eyelids

like sunspots bouncing on the carnival zoetrope

life is a view-master

powered by the sparks from briefly electric meat

it begins as a house

as breath on a window

as dew on the moss

bright and perfect, lingering just long enough

to evaporate

in the light that follows after

the sea captain’s daughter had salt stitched hair

kelp haunted fingers, a gallows-marked neck

her shoulders rolled with the song of the tide

and her boots struck sharp on the old sleeping townthe sea captain’s daughter held the moon in her teeth

whispered words running rat-like

down gutters, down vennels

into the guts of that old seaside towngood folk locked their houses

held fast to each other

their backs shook with the wind

that slapped the shutters, a red-handed lover

held fast to each other

shook with the wind, and more than the windthe sea captain’s daughter pulled her collar higher

sent the shiver in her hands back out to seasang a little song of coral

and parrot-fish

and darker thingsdamp were the lips of the sea captain’s daughter

and raw her knuckles under light of the storm

and the watch that called her did not move herfor the sorrow on her back hung like a sou’wester

the skin of a shark slipped over her bonesand the men that came for her

had hands that sought murder

lit with torches held blazing and bright_

the torches spat fire

spat fire in the old town

out over the ocean and into the nightthe ship captain’s daughter ran steel over her fingers

over the cobbles of the town

slick, and slickening

sang a song of cat-bone and flint

wiped her blade clean

or clean as blood comes

on these cold nights, in these cold sea-side townscalled out for her father

ringing like a bell

called out for her mother

sighing like a dove

called out for vengeance

soft as starlightand the good folk of the town

hushed their lips, lidded their eyes

held their counsel

like a dog holds a harethere was spite in the heart of the sea-captain’s daughter

green as glass

hope in the heart of the sea-captain’s daughter

slight as sadnessher voice slid through the town

slunk like a cat

soared like a weeping bird over tile and tower

kindled a flame in the hill-house

kindled a flame in the bed where her father sleptand the ships slept in the harbour

where boats knocked like babes against their sides

where songs spilt over the wreck of the pier

and her crew waited with wet eyes

waited with wet eyes, and thundering heartsthere was salt stitched in the hair of the sea captain’s daughter

a scar stitched on her brow

a limp stitched in her leg

and hate stitched in her heartwicked and wending up the hill

her voice like a ragged owl’s call

her tongue bright against the dark

bright against the steering starsand a flame kindled in the hill-house

and a door unlatched

and the shape of her father against the fire

against the hearth, against the darkthe sea-captain’s daughter held heartsblood in her hand

written on paper, sealed and witnessed

held heartsblood in her hand, thrust against the sky

against the stuttering starsthe good folk of the town turned their faces from the hill

from the gallows

from the graveyard held at its back

from the well-worn track that sent one to the other

turned their faces from the hill

sang pale, coward songs to each other

behind closed doorsthe sea captain’s daughter had fire in her feet

a blade in one hand

still wet with wanting

a baby in the other

hushed to sleepingthe shape of her father

a shadow, speaking

the shape of her hope

like a lit wick gutteringa choice that hung on a twist of the gallow’s rope

on the blade in her right hand

or the babe in her left

a choice that hung in the cold night

of that cold sea-side towna whistle on the lips of the sea-captain’s daughter

a wail like wolves from her crew below

a wave that hits the good folk of the town

that drowns them in bitter battle and bloodand the shape of her father is sorrow

then rage

then nothing

fading in the fire’s lightthe sea captain’s daughter has salt stitched in her hair

strands of kelp still haunt her fingers

the mark of the gallows hangs on her neck

but her baby rocks slow by the hill-house fire

and she smiles, soft

soft above the smouldering town

he lies on the stretcher

the bones of his face lightly tanned with his skin

like vellum under lamplight

the soft shadow of his eyes smudged under his brow

remembering the black on the fingers that moved printers’ blocks into place

shapes into speech into stitches into shapes into speech.

his thoughts flicker against the back of his eyes as his lips and teeth seek air, find rubber.

the light washes the room, now red, now blue.

in the corner, my grandmothers knits her hands over tight lips.

if bone could unravel, we’d all be undone.

But it stays

in the glare of the light

like the last filament

before the bulb breaks

down into dark

She works in an office. You know the type, grey wool suit, hair in a neat bob. By the water cooler, little paper cup in reasonably manicured hands.

Wait. I should say, she used to work in an office.

There aren’t really any office now, just their hollow skeletons, gently mouldering down to damp, strung with the cries of investment managers.

We closed most of the offices after the pandemic had run its course.

Didn’t really see the point anymore.

Fired a twnty-one gun salute for Pret a Manger and went on our way.

Nowadays we still go through some of the motions. Little genuflections to capital, performing business. She still wears her grey suit, still types at her keyboard, but there’s earth under her nails.

Once the webcam is off she loses herself in the hedgerows, gathers blackberries, stripes her legs with thorns, stares into the blue of a robin’s egg.

Comes home nettle-stung under the moonlight, every muscle aching, eats a supper of bitter leaves and dark bread, sleeps sounder than she has in years.

The photograph is predictable in many ways. A standard holiday snap. Me and my dad on a donkey.The donkey has been decorated with typical Spanish restraint. Every inch of its harness is beaded with intricate patterns that shift and click when the flies orbit in little, biting, parabolas.There are flies because this is Spain, and this is summer, and as my grandmother said, ‘God has to curse a perfect nation to keep it humble.’My Dad is decorated with typical Dad restraint, which is say he looks like a hotel maitre d’ who has broken loose and stumbled into a disco on his way to freedom.His eyes are bright and his smile is perfect.His hair would date the photograph if the pattern on my shorts didn’t already do the job.I am dressed as all toddlers are dressed, like a sticky potato with big eyes and ambitions. I clutch the donkey’s reins mercilessly.Everything about the photo is as I remember, except, it is in black and white, which confuses me, because everything about that day drips colour.

after Sheila Dongautumn will come and the hills will rejoice

mist will fall on their bones and the wet

feathers of birds will stitch a blanket

amongst the damp trees

the earth will thrum with mushrooms

and we’ll gather the last spent cases off the moor

while the dogs bark at the ghosts of grouse

autumn will come and we’ll put our shoulders to barn doors

swollen with the rain

sweep out the old straw and strop the scythes back to sharpness

we’ll stoke fires in the old hall

where the delftware tiles are smudged with smoke

and our knuckles ache on the colder mornings

autumn will come and we’ll admire each others’

windkissed faces

pull our jumper sleeves over our hands and set the table

the same size as always

but with a few less places every year

He counts every strand of the net as it slips over the side.Winces as the hawser bucks and screams in the salt gale and hauls faster.His eyes scan every frayed twist, every ragged hole where something big has chewed its way loose.His heart quiets a little as the silver fish start to tumble slickly over the dock.He starts to count coin in his head as his breathing slows.It doesn’t last. The wind skirls upwards and the entire ship twists in the gale like a breech-born baby.The clouds on the far horizon cough ozone greenly into the water and he feels electricity run the edges of his teeth.It’s two hours back to harbour and the storm walking over the tops of the waves will have him blood, bone and rust, long before that.He spits on his red raw hands, grabs the net and hauls.

They came at first in ones or twos.

Thin dark boats limping into harbour, oil lamps sputtering on their prows.

Thin boats, slipping into harbour like a skelf under a nail.

Thin boats with thin crews, their gelid moonfaces slick with tallow fat, bobbing on their salt-bent spines like fish on a lure.

Ones and twos at first, but gathering as the tide swelled.

Thickening the scoop of the harbour with their blackwood spars and their foreign songs that hung over the water like the oily smoke from their sputtering lamps.

We stowed their thin bodies as best we could in harbour beds and dockside attics. Listened at night as they sang to each other, as the strange sounds of their speech fell past the rats in the walls.

They were fleeing they said, fleeing an ocean turned black, where the ice-floes boiled to the colour of blood and the fish turned sour from the air in their lungs.

We laughed at them, stocked their holds and wished them well. Watched them sail out and enjoyed the quiet they left behind them.

Thought no more about them, about their thin bones and smoke-slick faces, until the morning that the waters ran black and beyond the sea-wall the ocean was cut with red ice, studded with the pallid eyes of gasping fish who withered in the curdling air.

Avenencia (Agreement)The closer my family gets to death, the more I think about the shape of that family.

In particular, I think about those family members I never got to meet, and particularly about my grandfather on my father’s side.

Here are the things I know about my grandfather:

That he grew cotton.

That he loved chicken.

That he was bitten by a snake on the thigh.

That he lost an eye fighting fascists in the Civil War.

And that he owned a venencia.

I’ll assume you don’t know, but a venencia is used for pouring sherry.

It is a whip thin piece of metal, flexible as memory (we call this the vastago), with a steel cup at the head (we call this the cubilete).

The vastago used to be made from a whale’s whisker. A shallow, sweet swim.

Nowadays, it’s made from PVC.

The venencia, whiskerless, is used for retrieving sherry from deep within its dark wood barrels.

It goes where it might otherwise be impossible to reach.

When you withdraw the venencia you flip it dramatically as you would your hair in a L’Oreal commercial, and decant it from no less than one metre, into the sherry glass.

Understanding my grandfather feels like becoming a venenciador, reaching back over a great distance, stopping into the darkness, and decanting something bright, strange and unfamiliar on the tongue.

There is a crack in his tooth that flickers when he talks.

He is explaining the cost to me, his parched brown hand shifting over leaflets and paperwork

His voice is soothing in the way that boredom is soothing, in the way that waiting for something leaves a space in which you can’t do anything else.

I try to follow it as he enumerates the efficiency of a plastic urn, the benefits of a rosewood finish, but there is a crack in his tooth that flickers when he talks.

Sometimes a little bubble of spit gets caught there, sparkling like frogspawn.

He opens folders that smell of offices, presses brochures into my hands and slips a pen with a chewed cap between my fingers.

I look at the marks of his molars again and think of that little crack in his teeth, wriggling like wormsign, flickering like a shadow against the bone.

Long after he is gone, and I’ve headed to bed, I lie in the dark, the brochures on the bedside table, my eyelids closed and I imagine his half-smile hanging in the blackness over my bed, white and watchful except for the crack in his tooth that flickers when he talks.

What we learn in the dark remains all our lives

and what we live in the dark lacks shapes we have tongues forand what I’m trying to say is

becoming yourself is an act of forgettingwhat we learn in the dark is archaeology

and the moments we spend there leave traces on our eyes in the day

like spots against the sunif everything we knew about ourselves could be catalogued

it would lose something in the archivingour sweetest truths slip like cryptids between the trees

and our regrets dance in the pixels of an untuned camerawhat we learn in the dark is to glimpse sideways

to look askance at things we once held familiar

to enter the cathedral by the side door

to skip the crowds

and on approaching the altar

find it bare of anything

but the light falling from old soft glass

Those mornings, when I woke unbidden

when the steam from my breath and my piss misted

because we had let winter into the house unknown

during the night

the streets had drawn close as we slept

wrapped around us in the dark

when we woke

we shrugged them off

in tarmac coils

Brewed coffee in the pot

let it dance black on our lips

watched the pans on the stove

and unfurled our fingers from clenched palms

one by one

when the phone rang we answered angrily

thinking

who are you

to come into this life

this space

where the only unwelcome guest

is the cold

The night of the great jailbreak began like any other.

A dun-coloured evening, the streets holding dust and sunflower shells.

The abuelas assembling on the street in the soft black of cats. Exchanging gossip over brown knuckles, grateful that the sweat-stained backs of their husbands were still cooling in the cotton fields.

Little pajaritos all solemnly hung from their doorside hooks.

The abuelas moving like lamplighters with feathered wicks, stringing the street with prisons that sang in liquid, looping tones.

When the first bird slipped the latch, it was barely noticed. By the third, fourth, fifth, their passage could be tracked by the laughter and screams. By the tenth, the twentieth, the abuelas has assembled an army armed with brooms and mantillas to beat them back, but it was hopeless.

The little pajaritos gathered themselves into a sweeping, swirling cloud and, still singing, ascended on the sound of a thousand tiny lungs into the night, leaving behind only the dusty heat of the day, the curses of las viejas and a few disgruntled and disappointed cats.

There is no name for this strip of land.

It has fallen out back of the old hospital.

It has grown, separate, shielded by oaks and rhododendrons.

The kids burn plastic here, in the shadow of the abandoned school.

Within its song of empty windows, yellowed paper.

This space is filled with the shards of other spaces.

A computer case. A ripped dress. A rug that has rotted to centipedes.

It is always wet here.

Always mould green. Moss green.

There is no name for this strip of land.

But buzzards hunt here.

And sometimes, on the wet mulch

blood

and sometimes, beneath the sag of an office chair,

the white strip glimmer of bone.

for Ivor GurneyHe heaves it everywhere he goes.

The thunder of blood beneath the storm.

The fall of blood beneath the rain.

The fall to emptiness,

arterial.

every night, the valves and chambers

of his heart opening and closing.

relentless relentless relentlesshe tries to cure it with walking

tries to silence the blood inside him

by moving his body over the milesten

twenty

thirtyuntil he’s shaking

the shake of the arms, the shake of the fingers

the shake of the bloodit drives him beyond distraction

he marches to war, and the blood marches with him

he writes music with the sound of machineguns

plays it on cellos, but the sound of the blood persistshe tries to fade it pianissimo

but in the sound beneath silence

there is still soundhis friends try to help him

they leave windows open at night

find him asleep on the sofa

in the morning, wet dog exhausted

the sound of the blood rising with the dawnalways he carries it with him

to the hospital

to its white walls, to the river

to the shallows by the willow

never releasing to flow downstream

always thundering

never gone

four apples, knife split

browned and bruised by

tumbling, tossed into the

dark earth amidst the bamboo canesa tail-less blackbird follows after, tapping its beak into the mush~‘It’s sair’, he says, ‘Look, it’s sair, it’s bruised where the needle’s gaun in and your chemicals are coming oot. It’s turning ma airm blue.’

‘Ugh. It stinks.’

‘It’s sair.’~A WhatsApp group chat.

176 participants.

Titled, slightly ominously, La Familia.

An endless buzz as the notifications come in.

¡Hola! ¿Como estas? ¿Que tal? ¿Que pasa cabron?

An endless parade of nieces and cousins in feria dresses and football tops.

Below it all like a back beat:

la vacuna la vacuna la vacuna la vacuna~Rotted apples in the dark of the garden, half-melted into the fox-soil and strawberry runners.

The fridge glows with yellow syringes and whole-fat milk.

The knife already set out in the quiet.

Ready for one more swing at the apples in the morning.~

summer collides with the cornfields

scatters the white tails of deer

over dirtbike trails

the second half of my life will be glossy and riotous

precariously balanced on twigs and fenceposts,

on the green of garden wire

the second half of my life will be stolen strawberries,

centipedes and beetles

slithering down the back of my throatthe burnt fence-post red of dusk and the brick haze of the old schoolthe second half of my life will be woodlice in the rafters

and the creak of the pine trees under the bulk of the moon

the second half of my life will be

boundless,

looped over cornfields

duelling skylarks for joy

screeching the heart of my waking

straight into the rising sun

[Selections from cabinet text, National Museum of Scotland]An electrostatic head, unsigned.

Mounted on an unrelated antique bust.

Scrolled legs, dating from the regency era.

A selection of articulated joints.

Allowed to fall under their own weight

A number of missing attachments.

Purpose unknown.

Pre-Cambrian skull structure.

Flecked with chunks of Pyrite, fool’s gold.

A thousand points of light.

Carried into battle by warriors of the period.

Reflective of the attitudes of the time.

Primarily designed as entertainment.

Not the largest of its kind.

Likely having travelled thousands of miles.

Across the ocean

One hundred and seventy feet of water for every ten of land.

Valuable by dint of its sheer survival.

For though the world is destroyed in one part

it is renewed continuously in another

Prophets in the forms of birds

the branches of trees their hymnal

and their incantations run

rik-a-tik

down the spines of forestsProphets in the forms of birds

their wings a quiet clatter against the sky

the dream of them beyond a window

that holds chipped cups

grounds

waitingProphets in the forms of birds

wasp-beaked and quarrelling scripture

out into the branches

down into the leaf-mould

unheededProphets in the forms of birds

and a weight in the heart like a great black stoneProphets in the forms of birds

shrink-wrapped sandwiches

wet plastic, damp boots

a weight in the heart like a great black stone

that bows your trees, your ribsFingers on the dial and an empty tone

that suck the pips away

down the phone lines

Replacement clicks, kettle hisses

chipped mugs, grounds in the sink.

fingers on the windows and

prophets in the forms of birdsWorm-beaked in the hedgerows

shuddering into unshaven bodies in bars

flying home booze-soaked and hammer-hearted

unheededTwo sugars in the cup

rain in the dark earth

and blood on your lipsProphets in the forms of birds, leaf-twitched

and fractious

a tone in the ears and the buzz of distant cutting

a weight in the sky like a long worn coat and branches

that sway beyond lit windows, lit homes

boiled water and stale spicesProphets in the forms of birds

light-boned and soaked through

cosseting each other in moss robes

licking scarred trees, picking up splinters

a weight in the heart like a great black stone

The Lang Cut Tree stauns on its ain

it disnae fash itsel' wi chatterin'

it disnae hauv a gender tae get het up aboot

it wis never a part o' the patriarchythe bare bane o' its finger stabs the sky

Sayin', here, See me?Ah'm deid an' no deid.

Ah'm life and no life

Whit are you?The Lang Cut Tree has nae e'en

jist the skirlin circles o' veins

opened by the knife o' the windit sticks its muckle tae in the grund

and saysWhit are you? Whit have you seen?Ah've seen the sun bleed copper

Ah've seen the powrie-kissed stanes crack

in the winter frost

Ah've held up the clouds as they poured rain on tae

the sodden backs o' stoic sheep

hoachin up and doon the mountainWhit are you tae me?The Lang Cut Tree has nae lugs

jist the skelpit scars o' the worms that

eat itit flings its yin rib against the sky

and saysWhit are you?Ah've heard the logbone crunch of the longships

The banshee cry of mithers gaun daft

Ah've sucked in the song o’ the skyWhit are you tae me?

‘I dreamt of wolves last night’, she says, ‘first time.’

Her fingers drum nervously as she speaks.

I sip coffee, lick my lips.

‘I think that’s normal. Everybody dreams.’

She frowns, chases toast crumbs around the plate with a finger.

‘I don’t know. This felt different somehow. Familiar.’

I smile, kiss the top of her head and gather up the dishes.

She leaves for work soon after, aspen trees bending in a summer breeze and her white jacket slung over one shoulder.

I take my time after that, stretch, enjoy the warmth seeping into the room, watch the dust motes dance, hear the slow heartbeat of the house picked out in ticking clocks and the gentle settling of attic beams.

After a while, I open the door to the basement. I slide the key back on top of the bookshelf before I slip slowly down the stairs, feeling them bow and bend beneath me.

It’s where I left it. The bare brick of the basement wrapped around it like a lover’s fist.

I pull the strip light cord and the walls flinch from the snap and buzz, throwing its contours into relief.

The thick swoop of its brow, the hungry curve of its canines.

The skull is beautiful.

I kick off my heels and kneel on the floor in front of it.

My hands shake as I reach for it, but once I make contact, that stops. My fingers run over its hungry curves.

I stare into its empty sockets and let the breath slide out of my lungs, ragged and wet.

The old ache at the base of my spine hums in protest and I tuck my ankles further under my hips, wriggling.

My hair seems loose. I can feel every strand on my head, pressing down terribly.

I want to take it off. All of it. Take my nails and dig under the skin and peel, until all the mess and fuss is stripped away. Until I’m pale, and hard, and beautiful.

I stop my caresses briefly and dig into the pocket of my jeans.

Hair, blood, spit.

Plenty of it if you knew where to look.

People are aggressively biological. I wonder how they stand it. How do they carry it? The sheer weight of it.

All that meat.

I weave the loose strands around the teeth, slick the brow as best I can, my hands steadying as I work.

After that, everything else is simple by comparison. I lift the skull and spit in each eyeball, once. Press my head against the bony ridges and breathed deep.

There are hours until she gets back.

Endless slow hours, which limp past grudgingly.

I sing a bit. I dust. I move things around.

Eventually my voice fades away.

A little later, I forget what it sounded like.

I let its voice in to fill the gaps.

It is a rich thing, thick with the deep forest, nourished on pine and hot blood.

I hear it inside me, and I feel my ribs stretch with the possibilities.

Drop to all fours, run around, let my fingers scrabble against hard things, sink into soft things.

I come to after a while, naked in the hall.

I dress again, re-braid my hair and put dinner on.

Not long now.

I lick my teeth from the back, pushing my tongue forwards slowly.

I like how sharp they feel.

The door clicks as she returns, hair mussed, jacket crumpled.

I meet her in the hallway, hug her breathless.

She sinks into an armchair, kicks her shoes off negligently.

‘Hard day?’ I say.

She shrugs. Her shoulder blades shift.

‘No more than usual. You?’

Her mouth opens on the end of the question and I watch her lips.

‘Quiet’, I say. I flick my eyes down. ‘Better now you’re back. Dinner’s on’.

She smiles at that, but I can see the effort it takes.

I step behind her, run my hands through her tangles and think about lifting it all free.

I let my hands rest either side of her neck and push pressure down through my fingers. I can feel the tension knot and release.

She moans quietly in appreciation.

‘I missed you’, I say.

Her head tips back and I kiss her forehead, letting my teeth just touch her skull. ‘Shall we eat?’

It’s quiet while we do. We’re past the point where we need to fill space.

I pass the time by watching her, the curve of her legs, the quick movements of her fork, the earnest way she leans over her phone.

After dinner, we curl into each other and I feel her breath soften as she drifts off to sleep in front of the flicker of the television.

I run my fingers over the shape of her face, down her spine, over her hips.

As the light fades, its voice returns, pulled up by the white-bellied moon.

I listen intently and it speaks in the sounds of the deep places, the high valleys.

I hear ice on its breath and smell the wet rot of leaf mould.

She stirs in her sleep, and I watch her pulse play against the skin of her throat.

I sigh and I feel it ride my breath into the room.

The outlines sharpen and darken at the same time.

My world becomes stark, beautiful.

She’s a gentle weight in my arms as we climb the stairs and I tuck her in without fuss.

She sleeps deeply, her eyelids batting dreams which flicker fitfully across her brow.

I turn off the bedside lamp and open the curtains to let in the stars.

It’s a warm summer’s night, the garden wall hung with hot-brick scent and the footsteps of prowling cats.

I watch them go about their business for a while and it watches from behind me.

After a time, I hear her snores.

I brush her hair from her face and kiss her gently.

Straighten the covers around her and head downstairs.

Down to the walls, the flick and buzz. The solid sharpness of it in my hands.

It comes back upstairs with me, a reassuring weight in the moonlight.

I can hear its song in my head, feel its weight on my back, the long loping strides of its legs pressed against my own.

Carefully, reverently, I set the skull down on the bedside table and wait.

She stirs, quickly now. Faster than last night and the night before that.

She’s dreaming. Dreaming of running across tight-packed snow, under the jagged shadows of trees.

Of chasing and catching.

Of the copper-kiss of blood and the feel of teeth on meat.

Of strong bones, clean and bright beneath the moon.

I watch her forehead crease, hear her whimpers and reach out a hand to stroke her brow.

I can feel her beautiful skull. Just beneath her worrying skin.

It’s not easy to watch her like this, but I run my tongue across my teeth and think how happy she’ll be once she sees what she can become.

Once she steps out of all the heat, and the weight and the burden.

Once she hears its voice like I do.

I sit next to her as she dreams, and I hold her hands tight.

The things we do for love.

they're burning souls on the edge of the field againsetting blessings and bones loose intothe july skysending whiteness to whitenessleaving the spaces between acridwith absence

with pigeon feather